How E-commerce recommenders work, Introduction

Buying stuff without actually stepping out is one of those things that has radically changed all our lives. In this post , I want to dig deeper into how recommendations power online shopping. There is a lot of machine learning and also a fair amount of business practicalities and seeing how these systems are designed can teach us a lot.

Some context

In the bad old days of the internet, e-commerce websites were simply digitized product catalogs. Users had to explicitly find what they wanted either through search queries or navigating through category links. Recommendations were manually curated and were of the “top sellers” and “new products” variety.

With a catalog that could be in the millions, users had a hard time discovering products. Amazon which had the largest product catalog and user base, was probably the first to algorithmically generate recommendations in the early 2000s, using a family of techniques loosely called “Collaborative Filtering”. After twenty years, algorithmic recommendations are at the very core of our digital lives.

An Overview.

Users want to discover products that they did not know about. Websites want to sell more stuff. Meeting both these goals is what recommendations are about. When I first began working on recommendations, most of the research was on the MovieLens dataset (made famous by the Netflix prize) and I mistakenly thought that there was one monolithic algorithm that powered recommendations.

Recommendation algorithms are actually a large and diverse (pun intended) family of algorithms that are best thought of as different strategies for different stages of the user journey. E-commerce websites generally have three main kinds of pages. Here’s how platforms think about the user journey.

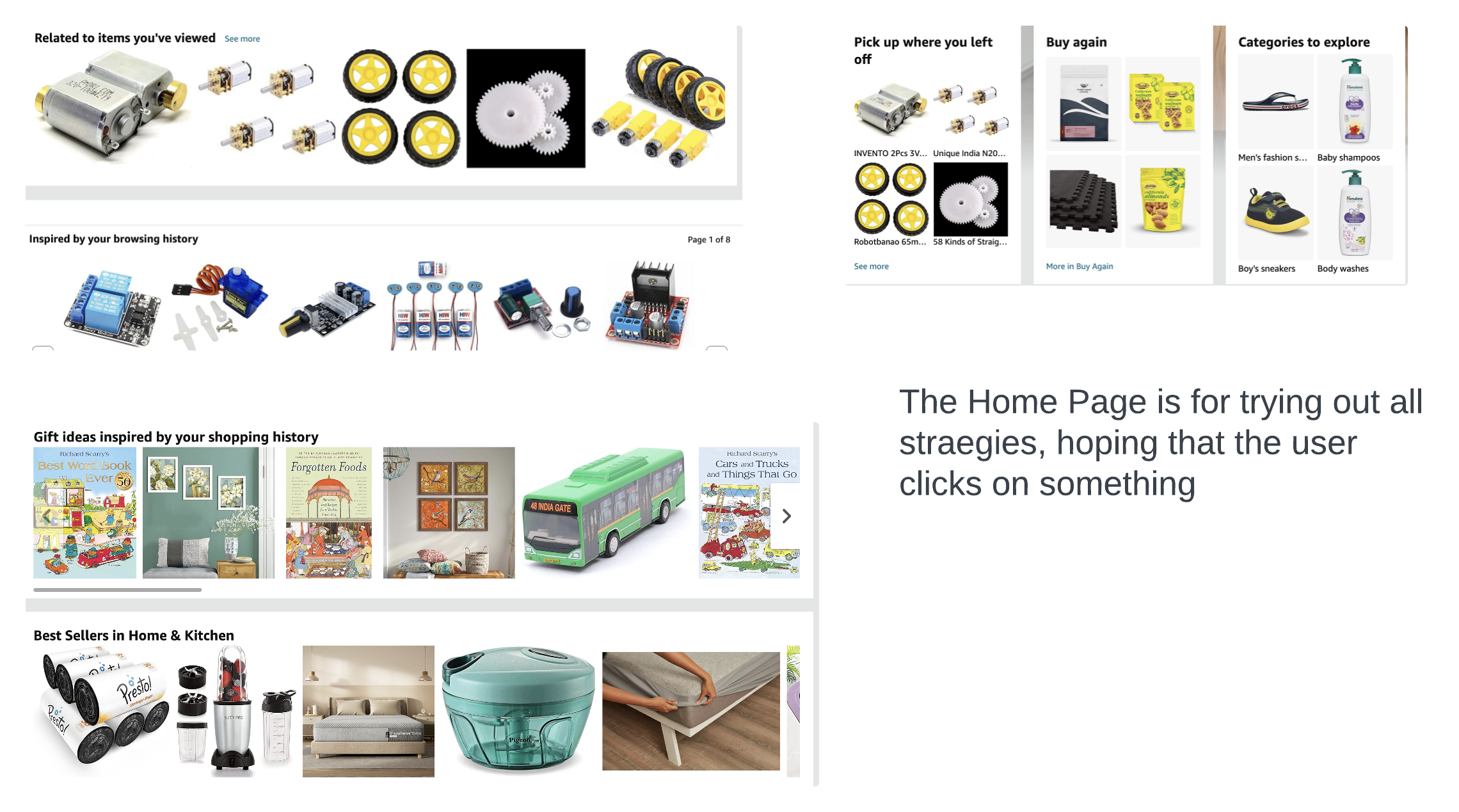

Home page.

This is the starting point. For users who have past interactions, this page usually has recommendations that are personalized for the user’s assumed intent. Intent is much weaker here, so this is a place where platforms use a scattergun approach to show you a whole range of strategies, hoping something would click.

- Recommended for you. Products that you would want to buy next. The classic personalization strategy.

- Continue shopping. Products that you have viewed recently. This is a simple strategy, with no ML, but works really well. Users already have an intent to buy these products

- Buy again Essentials that are likely to be purchased repeatedly. Nobody wants to run out of coffee or diapers

- Best Sellers. Not usually personalized. But these do extremely well and are a good baseline to measure more personalized strategies

- Promotions Feature current deals. These are usually not personalized beyond geography or past categories that the user has interacted with

Recommendations on my Amazon Home Page

Recommendations on my Amazon Home Page

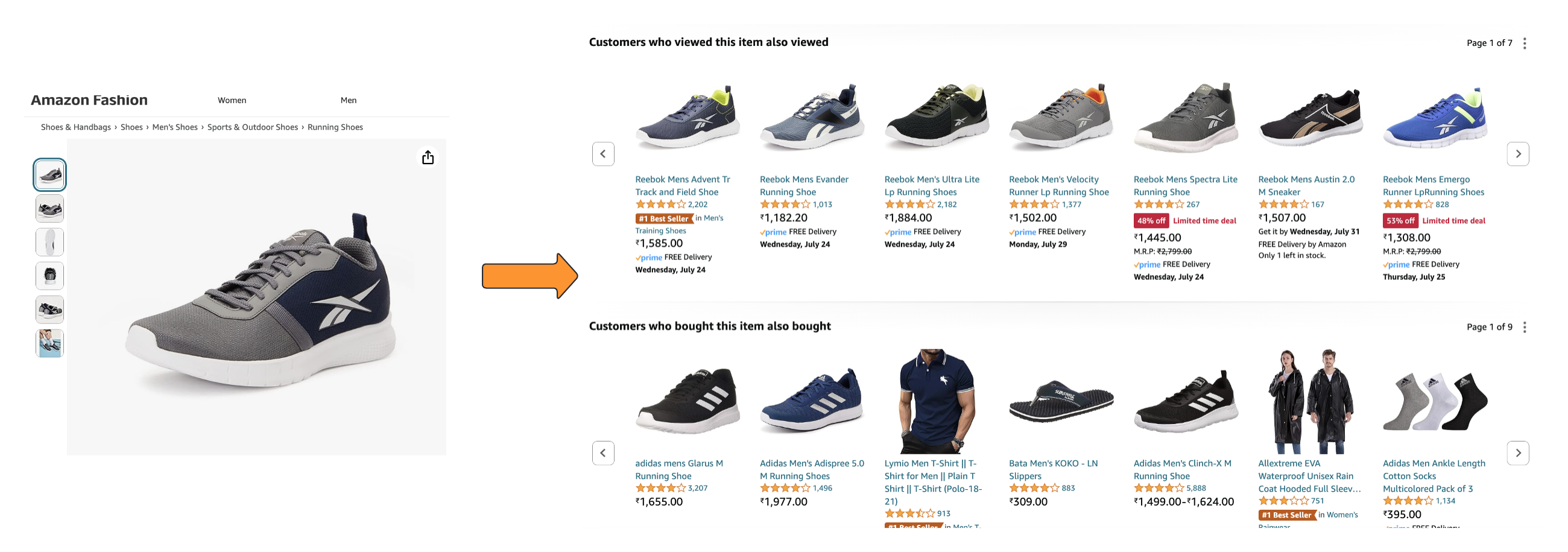

Product Page.

Users who show up here either through search or recommendations already have a very strong intent to buy. This is the meat of the recommendation engine. Most of the revenue that flows through recommendations comes from these strategies.

- Related products. This is probably the single most important strategy. Users explore similar products before making the final purchase. Related products are computed offline and any personalization for the user (if at all) can be done by very lightweight ML models. Related is a broad term and can include similar or complimentary products. Looking at past user interactions (view, add to cart, purchase, etc) is the standard way to generate these. For example, two products that are often viewed together in a user session are likely to be similar. But products that are bought together are probably complementary.

Recommendations on a Product Page

Recommendations on a Product Page

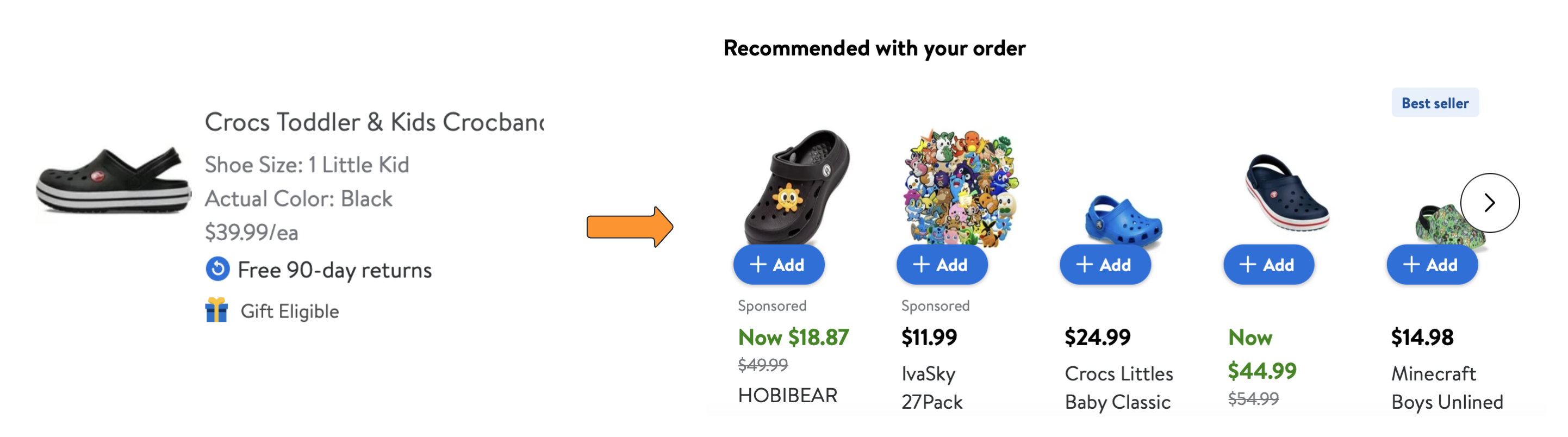

Cart or Checkout Page.

These recommendations are based on, what’s already in the user’s cart and feature complimentary products and accessories. These are also not usually personalized and can be computed offline. Using past purchases by all the users and filtering based on “nearby” product categories is usually how these recommendations are generated.

Recommendations on a Cart Page

Recommendations on a Cart Page

This is only a rough separation and platforms are happy to fill the entire page with as many recommendations as the eye can take in. The old explore vs exploit tradeoff has been solved by basically doing both at the same time in different strategies that fill up the page.

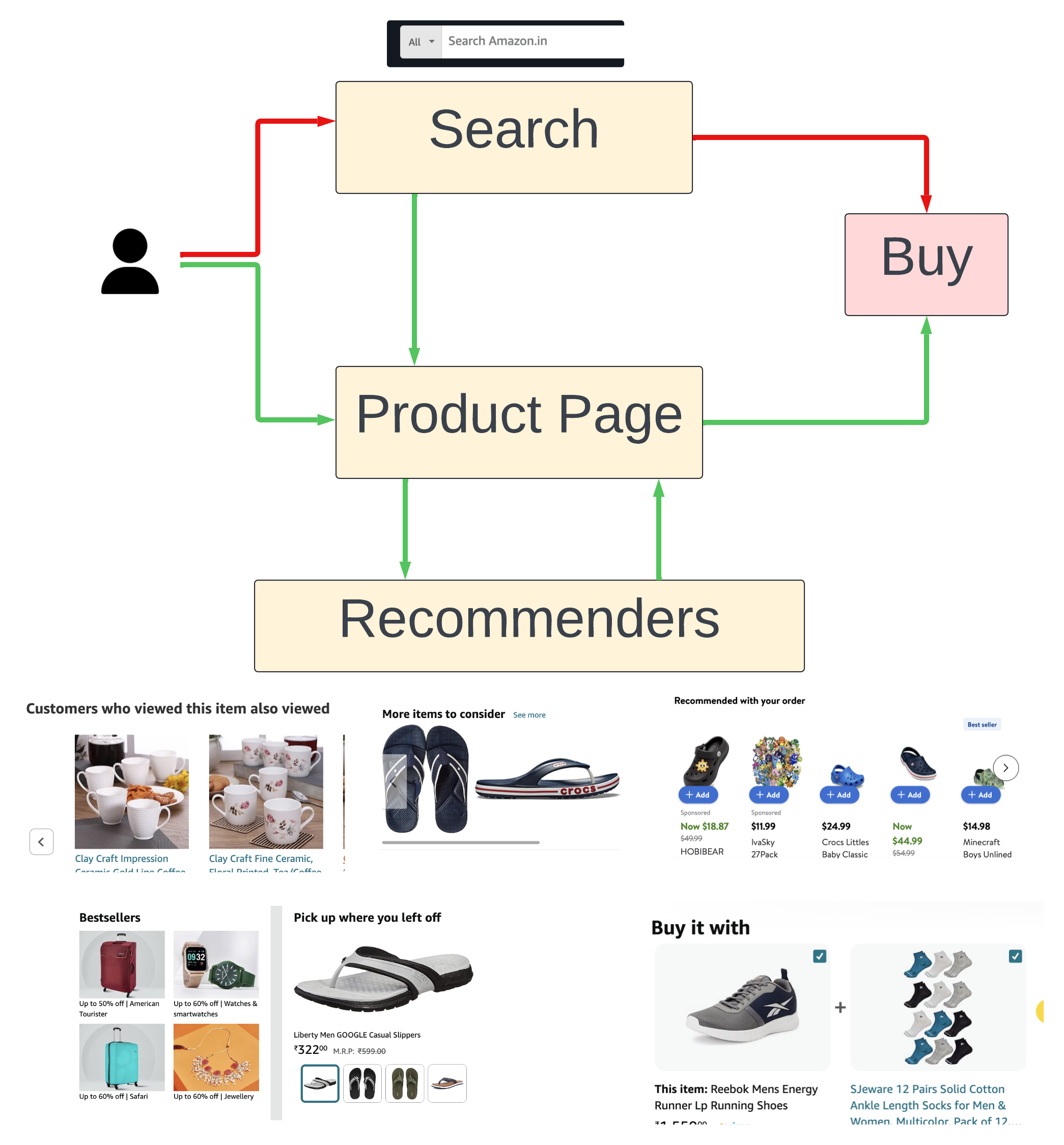

The Data

Take a look at the simplistic user journey in the figure below.

User journey. Green arrows are for recommenders

User journey. Green arrows are for recommenders

Every user action (like a page view, search, add to cart, recommender impressions, etc ) gets logged. Offline data processing pipelines sort these chronologically for every user and session. This interaction data, when aggregated across users and for a sufficiently long window of time, provides the fuel for recommender systems.

Product Relations can sometimes emerge from this, which might seem counterintuitive. For example, notice the recommendations for the kid’s Crocs (on the checkout page), including some very similar-looking crocs. Do users really buy a lot of Crocs together in one order? Perhaps, they buy a few and return the ones that didn’t fit.

Sometimes, when working on these systems, it’s tempting to use our own notions of ‘relevance’. In general, it’s best to use standard proxy metrics (like click-through or purchase) to measure any recommender system. Not that these are infallible, but it’s better than our personal judgments.

The Goal and Measuring it

The ultimate goal of all these strategies is to get users to buy stuff, they would otherwise not have bought.

By a very old estimate, about a third of Amazon’s revenue flows through recommendations. To understand what “flows through recommendations” means, it’s helpful to think of the opposite. When do purchases happen without any interaction with recommenders? When users type in a search query and directly click on a result and buy that. All other user journeys involve interacting with a recommendation and platforms count them as “flowing through recommenders”. This is the topline number for the overall recommendation system.

For individual strategies like “Related products”, click-through rate (CTR) and conversion rate (user actually buying what was recommended) are good proxy metrics to see how good the recommendations are.

If you like nitpicking, you will notice that these metrics do not actually measure incremental revenue (using a very strict definition of incrementality). What would happen if there were no recommendations? Users would still manage to find things using search. But the overall revenue would be drastically lesser. But just removing the recommendations and leaving behind empty space, will also not please the statisticians.

The fundamental question is what should you compare recommendations against? This is a very deep question and has no easy answers. To really measure how recommendations help the platform (and users) in the short and long term is an open question.

How e-commerce recommendations are different

I think the Netflix prize really kickstarted interest in recommender systems. As a result, a lot of the published research was around movies and ratings. The likes of Amazon were of course doing plenty in this space but were reluctant to share their secret sauce. In my experience, e-commerce recommendations are quite different from the Netflix, Spotify, or Instagram kind of recommendations.

Users mostly come to e-commerce platforms when they have an intent to buy something. Unlike, Netflix or social media, where users could just be browsing looking for inspiration (euphemism for endless scrolling), when users shop they are more focused. This means that most recommendations are about exploiting the user’s current need and hence strategies like “similar products” or “users who bought X also bought Y”, dominate. Apparel and home decor are perhaps exceptions, where user intent can be more about “inspiration”.

User’s needs change very quickly. If you like movies or music, you probably have a relatively stable taste, and recommendation algorithms can use your past interactions to recommend things. When shopping, however, one day you could be buying diapers, and the next day you could be buying a vacuum cleaner. User intent changes rapidly and looking at a long history of past interactions isn’t always very helpful

- Products have a rich and well-defined taxonomy. This is extremely important for being able to recommend complementary or similar products.

- Different product categories demand different recommendation strategies. For example, apparel and home decor are categories where users are more open to inspiration.

- Price is very important. Retailers want to maximize revenue (or profit margins) and users want to spend less. Price is usually used in some way to rank recommendations and this makes things messy.

- Business practicalities are important. Promotions, shipping costs, inventory, and a bunch of other messy retail things, mean that there is usually some sort of filter and ad-hoc heuristics applied to any algorithmically generated recommendations. This makes it harder to measure things that ML folks care about.

Lots of ML problems

All recommender systems have to deal with data sparsity. Most users and products have very few interactions. The mythical long tail is truly long for e-commerce. What to do about new users and new products is also another thing that requires some sensible heuristics.

Here is a sample of the more interesting challenges.

Scalability and Speed. Recommender systems have to respond in real-time to users as they browse. This means that a lot of the heavy lifting that goes into generating these recommendations happens offline. The early generation of techniques (inspired by the Netflix prize) involved matrix factorization and these are not scalable. Item-Item similarities can be computed offline and very lightweight ML models can run on top of these precomputed lists to generate personalized recommendations.

Embeddings for products. Using interaction data to create product embeddings is extremely useful for all kinds of downstream tasks. Techniques that were once used for text (like word2vec and friends) have found new and creative uses in e-commerce.

Graph problems. Thinking of products as nodes in a graph, where the edges can encode viewed-next or bought-next kind of relationships, opens up the problem to techniques like Graph Convolutions. This is another powerful way to learn product embeddings. Of course, we can also include search queries and other such entities as nodes. Now we can get similar searches, and even recommend products for search queries.

Product Taxonomy is rich. All products are leaves in a deeply nested tree. Using this structure as side information while generating recommendations is I think an open problem. Usually, taxonomy is used as a filter to weed out recommendations that can arise from looking only at interaction data. The famous beer and diapers example is something we don’t actually want to see

Meta-questions like which algorithms perform better for different categories. What works for apparel might not work for electronics.

Offline evaluation can often be misleading. Offline Evaluation of recommenders is notoriously tricky and often misleading. But you can’t A/B test every idea you have, so we do need some offline evaluation. The iteration time for any algorithmic change is long because of this.

I hope this long overview was useful in setting the context. In the next post, I plan to go into the technical details of the classic “Related products” strategy.

Further Reading

- Amazon’s orginal paper on item-item recommender system

- A classic overview of recommenders by the GroupLens group (who published a lot of the early work in RecSys)

- Another long read from the GroupLens group

- Amazon’s re-look at RecSys after 20 years